[This is the first part in a two part series on our team coming to grips with the implication of COVID-19 for two impacted communities.]

Scary times surround us. News of friends and family, of colleagues and partners, or supporters and contacts can bring on anxiety, grief, anger, and fear.Over the past couple of days we’ve learned what we always knew: that those who were already disadvantaged and at risk – in educational outcomes, in economic outcomes, in health outcomes – are suffering the worst from COVID-19.

Yesterday the New York Times described the chasm of inequitable outcomes in the transition to remote learning which largely reflect race and class divisions.

The Washington Post highlighted the campaign lead by Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law to ensure that COVID-19 infections and deaths are dis-aggregated by race and ethnicity. Preliminary data is infuriating; in Louisiana, for example, the black community represents one-third of the population yet 70% of COVID-19 deaths. The Chicago Tribune describes how the black community is 6 times more likely to die of coronavirus as white people. It would be naive to think this pattern won’t continue in other locations.

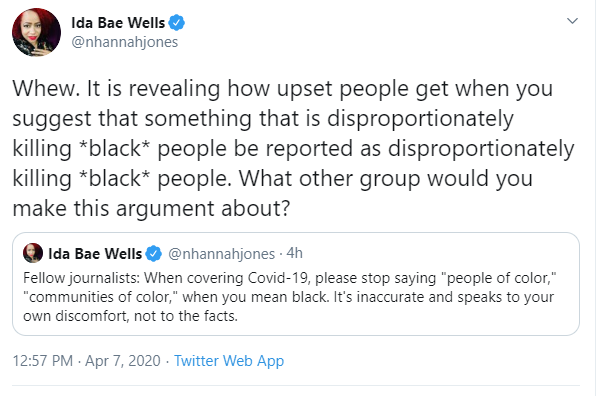

The simplicity of the Nikole Hannah-Jones’s request proves the power of anti-black racism in our language, our society, our health and educational outcomes. In The HIll, strategist Antjuan Seawright reminds us that the risk factors for COVID map directly onto the challenges of the black community:

- Asthma rates among black families and children are 20 percent higher than white families;

- Black families are 40 percent more likely to have high blood pressure;

- Diabetes diagnoses in black communities are more than double that of whites.

This is why we focused our Communities of Practice work so much on building anti-racist culture and curriculum and why we made “Intentional Integration” the them of our 2020 convening.

It’s why Mohammed Chowdhury challenged us and those in education reform that “Until we decouple whiteness with privilege and power resources, integration must be a strategy.”

It’s why, as she considers how to get bolder, Cheyenne Batista constantly questions “what do I bring to the stage and what do I name? Can I name whiteness? Can I name white dominant culture? Can I say the words white supremacy without a cost to my career and credibility?”

It’s why EPIC Theater Ensemble used our convening in DC to help us remember to not beat around the bush of white-supremacy.

And, it’s why we must remember that there are bright spots to keep us inspired and moving forward. As always we start with our members.

- We were so impressed by this video roll out of remote learning to BUGS in Brooklyn.

- Yu Ming designed this page including a TOP 10 hacks to get mandarin into your kids life.

- Boston Collegiate launched this helpful webpage for their community.

- City Garden Montessori shared messages around beginning with mental health and social connection in the first few days of the transition to remote..

- Success Academy put together their remote learning plan starting with their guiding principles:

Despite the fear, anxiety and grief that surround us, we continue to look to our members as the beacons who will guide the way to the other side of this challenging time.

– Amy, Ashley, Dave, Seon, Sonia